Photo credit: Jaccob McKay/Unsplash

The following is a summary of the Lighter Footprints event “CARBON CREDITS: Dodgy offsets or the real deal?” held on Wednesday 27 July 2022. The recording is available here.

Moderator Tim Baxter, Senior Researcher for Climate Solutions at the Climate Council, introduced the event, making the point how timely it was given the election of a new government and the Chubb Review into the credibility of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs).

Tim gave a brief history of the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) pointing out NSW had the world’s first mandatory carbon price, under the NSW Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme (2003-2012). This was followed by a national scheme, the Carbon Farming Initiative, a voluntary carbon abatement scheme, which then became the ERF in 2014. To date, the ERF has 114 million credits to 1537 projects using over 50 methodologies. Each credit, one ACCU, represents the avoidance or removal of one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2-e) GHG. 114 million credits is about one-quarter of Australia’s annual emissions.

Most projects involved land regeneration, landfill gas and avoided deforestation as shown in the following table.

| Total credits issued |

Value of government contracts | |

| Land Regeneration (456 projects on 2 methods) |

35,398,794 | ~ $1,400 m |

| Landfill Gas (133 projects on 5 methods) |

30,565,147 | ~ $260 m |

| Avoided Deforestation (75 projects on 3 methods) |

24,231,925 | ~ $330 m |

| Savanna Burning (96 projects on 4 methods) |

11,157,723 | ~ $170 m |

| Alternative Waste Treatment (23 projects on 1 method) |

3,576,272 | ~ $35 m |

| Reforestation and plantations (217 projects on 10 methods) |

2,971,279 | ~ $61 m |

| Others (537 projects on 26 methods) |

6,137,029 | ~ $420 m |

Tim then introduced some key terminology in the carbon credit space. The first was ‘additionality’.

Additionality

An ‘additionality’ test assesses whether a project or activity creates ‘additional’ emissions reductions that would not have occurred in the absence of the incentive. Additionality is important to ensure that a baseline and credit scheme does not pay for emissions reductions that would have occurred anyway. Additionality tests raise confidence that emissions reductions are additional or ‘real’.

Scope

- Scope 1: the emissions created directly by industry, e.g. its gas-powered boiler onsite

- Scope 2: emissions associated with the electricity used (electricity emissions occur at the power station, e.g. from brown coal generators)

- Scope 3: emissions outside the industry’s site boundary in the supply chain e.g. from transportation upstream and downstream

Tim then introduced Professor Andrew Macintosh.

Professor Andrew Macintosh

Professor Andrew Macintosh is Director of Research at The Australian National University Law School. He is a regulatory and environmental markets expert and was:

- Chair of the Australian Government’s Domestic Offsets Integrity Committee and Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee between 2013-2020

- a member of the Australian Government’s Emissions Reduction Fund Expert Reference Group in 2014

- an Associate Member of the Climate Change Authority in 2015-2016

- a member of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act Expert Review Panel in 2019-2020.

Andrew is currently a program lead for the Australian Government’s Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship Package and National Biodiversity Trading Platform. In 2020, he served as one of the three Commissioners on the Bushfires Royal Commission. Andrew Macintosh’s research has been published in prestigious journals including Nature Climate Change, Climatic Change and the Journal of Environmental Law. Andrew was awarded the Schlamadinger Prize for Climate Change Research in 2012.

Problems with the ERF

Andrew began by emphasising that he and his team are supporters of carbon markets. That their goal is to address the integrity issues around the ERF and improve it so that it can do the job it was intended to do. We need offsets to get to a low carbon economy but the offsets must have high integrity.

However, offsets are a “high-risk environmental instrument” that are easy to get wrong. Estimating abatement relative to a counterfactual is hard. If credits have low integrity and they are used by polluters to offset emissions, it increases emissions.

Proposed Rule

Only issue carbon offsets where there is high confidence they represent real and additional abatement

What went wrong with the ERF?

The majority of credits being issued do not represent real and additional abatement. This is because there are bad rules governing project eligibility and abatement estimation (bad methods) + poor interpretation/implementation of the methods by the Clean Energy Regulator (Proximate cause). But Macintosh and his team believe the ‘Root cause’ is poor governance and a lack of transparency.

The complexity of carbon credit schemes makes transparency challenging. It is easy to hide things.

Proximate Cause – bad methods and bad implementation

The ERF is not “economy-wide”, it is dominated by three project types (‘the big three’):

- Avoided deforestation in western NSW = ~22% of issued ACCUs

- Human-induced Regeneration (HIR) = ~27% of issued ACCUs

- Landfill gas = ~27% of issued ACCUs

So three-quarters (77%) of the program comes from the big three and there are major integrity problems with all three.

1. Problems with ‘avoided deforestation’

Allows landholders in western New South Wales to get ACCUs for not clearing native forests. It is based on the assumption that landholders who applied for and received a specific type of clearing permit would use them within 15 years. But clearing permits were substantially over-allocated, authorising the clearing of substantially more forests than would ever have been cleared, particularly within 15 years. This results in a risk that proponents would get ACCUs for not clearing forests they were never going to clear.

2. Problems with ‘Human-induced Regeneration (HIR)’

Human-induced Regeneration HIR, the biggest project-type, allows landholders to earn ACCUs for regenerating native forests. It was originally intended this would occur in areas that were previously cleared – a good idea, However, most projects were actually set up in semi-arid and arid rangeland areas that have not been comprehensively cleared (97%) – a bad idea. Most projects are trying to regenerate native forests in largely uncleared remnant native vegetation, purely by reducing grazing pressure from livestock and feral animals.

This map shows regeneration (blue areas) has occurred in arid zones well away from the cleared regions (light grey areas).

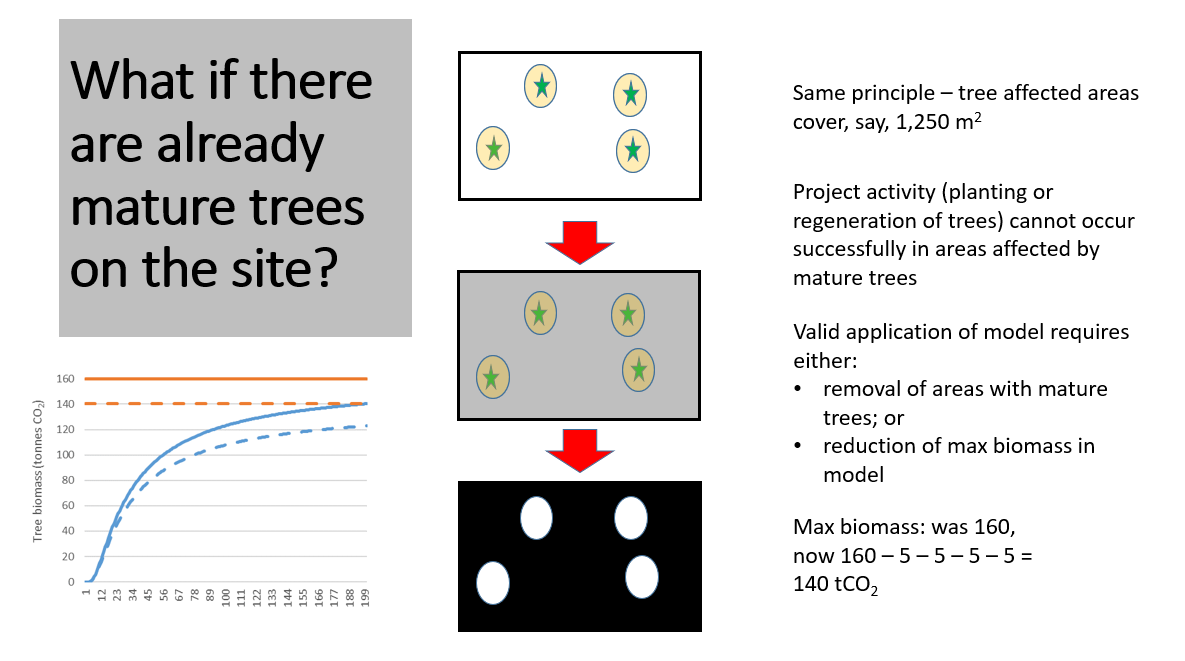

3. The ‘over-crediting’ problem

Projects are being substantially ‘over-credited’ because the model used to estimate tree growth assumes the areas have been substantially cleared (or >95% reduction in tree/shrub cover by another means). However, the model fails to take into account roads and existing trees, areas which could not or will not regenerate.

At the moment, proponents of HIR projects are receiving ACCUs to grow trees that were already there when the projects started! The model needs to be modified.

HIR additionality

Most projects claim they are regenerating native forests by reducing grazing pressure. However, science suggests grazing has a relatively limited impact on tree/shrub cover in rangeland areas. Grazing affects ground cover and biodiversity but has a limited impact on tree/shrub cover. It is extremely rare (if not impossible) for grazing to reduce woody biomass by >95% over significant areas as required. The rain-drought cycle is the primary driver of tree/shrub cover changes, not grazing.

Root Cause – bad governance and a lack of transparency

Carbon offset markets are ‘special’. In a normal market, the buyers care about quality, and sellers differentiate on the basis of quality which means there are incentives to maintain quality. However, in the carbon market, most buyers do not care about quality, and most sellers generally do not care about quality, which means there is elevated importance given to rule makers and regulators as the guardians of integrity. The role of rule makers and regulators is made more important by complexity and it’s very hard for 3rd parties to evaluate and track the integrity of offsets. The result is a need for strict separation of powers, radical transparency and processes to involve 3rd parties.

The ERF governance structures are flawed. There is no strict separation of powers/roles. The Clean Energy Regulation is the Rule maker, Regulator and Government buyer, and it staffs the Rule assessor. There is no transparency. The location of projects is published but not credited areas, the offset reports, audit reports and abatement estimation assumptions are not published. There is no 3rd party involvement. 3rd parties are given limited or no access to rulemaking and there are no 3rd party appeals.

A final caution, tightening up integrity will reduce the number of ACCU’s initially (the supply) and therefore drive up the ACCU’s price. So there is a need for a price cap in the Safeguard Mechanism to shield polluters from the impacts of any transition to integrity.

Conclusion

The ERF is broken. It has bad rules, bad implementation and bad governance. The new Government needs to intervene to ensure the ERF has integrity. The transition to integrity is going to be rough – vested interests are going to pay a price. A price cap on ACCU’s will be needed in the transition.

Ric Brazzale

Tim then introduced the second speaker Ric Brazzale.

Ric Brazzale is Managing Director at Green Energy Trading, an Australian environmental certificate agent and a clean energy market advocate. He works with clients in the areas of residential and commercial solar; water and space heating; air-conditioning, commercial lighting, and energy efficiency projects to make the most of renewable energy and energy efficiency certificates such as STCs, LGCs, VEECs, ESCs and ACCUs.

Ric is also Managing Director of Green Energy Markets and has been involved in the renewable energy industry for more than 30 years. He was on the initial Government/Industry working group that worked on developing and implementing the Mandated Renewable Energy Target.

Ric was also the Executive Director of the Business Council for Sustainable Energy, now the Clean Energy Council.

During this time, he was actively involved in the development and implementation of a broad range of solar energy and energy efficiency policies and programs, including participating on the Government’s initial REC Advisor Committee.

Ric is also President of the REC Agents Association and the Voluntary Carbon Markets Association and is a Board Member of the Energy Savings Industry Association and Solar Citizens.

What does Green Energy Trading do?

Green Energy Trading has been in business since 2007 with offices in Sydney & Melbourne. The company seeks to dramatically reduce greenhouse emissions by supporting clients to roll out clean energy solutions (solar, wind, energy-saving upgrades, batteries etc.). The company does this by monetising the benefits that these technologies deliver in reducing greenhouse emissions (supported by government schemes). The company originates ACCUs, Renewable Energy Certificates and Energy Efficiency Certificates.

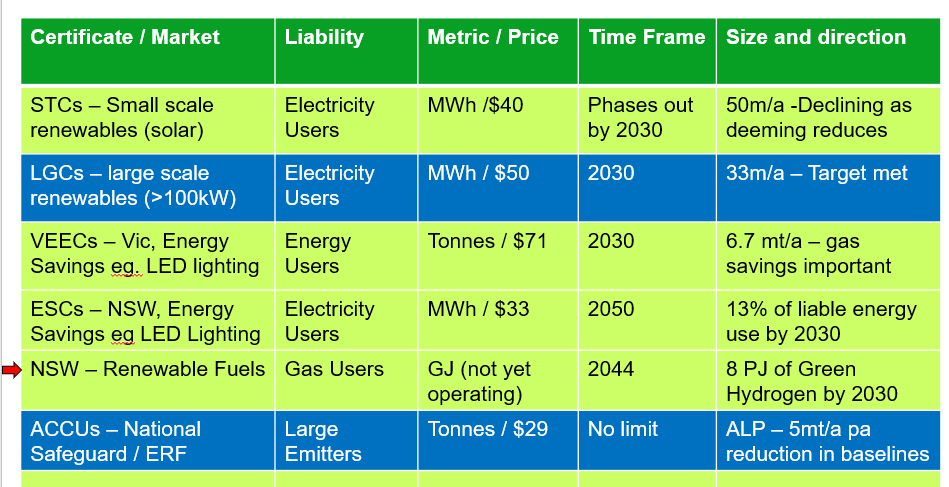

Range of Carbon/Offset schemes

The following table shows the diverse range of Carbon/Offset schemes currently operating in Australia.

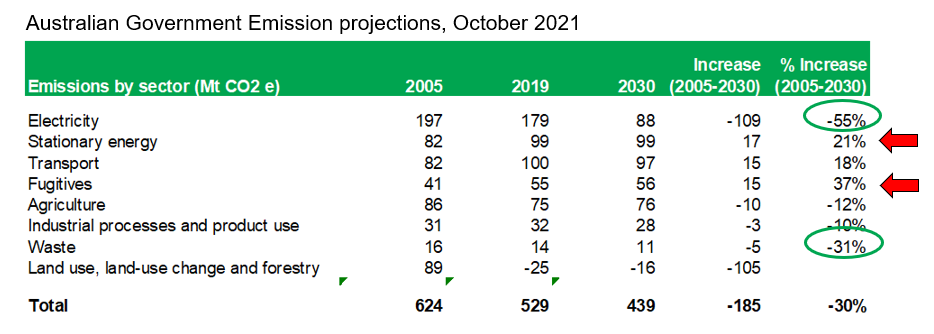

Electricity is doing the heavy lifting

As shown by this table, the previous government forecast emissions reduction of 30% on 2005 levels by 2030 with the electricity and land use sectors leading the way. Electricity emissions have fallen due to the Commonwealth renewables scheme and state energy savings schemes. However, stationary energy (e.g. emissions from LNG use in industry) and fugitive emissions (e.g. methane released from coal mining) have increased significantly because baselines under the Safeguard Mechanism have been ineffective to date.

How will the Federal Government deliver its 43% emission reduction target?

Policies

The new Labor government has policies to deliver an additional 89 Mega-tonne per annum (Mt/a) reduction by 2030 as follows:

- $20 billion Rewiring the nation – (37 Mt/a)

- Tightening Safeguard Mechanism baselines (48 Mt/a)

- National Electric Vehicle Strategy (4 Mt/a)

The Safeguard Mechanism covers 215 facilities that exceed 100,000 tonnes of direct emissions per annum (Scope 1)

In total, the facilities accounted for 140 million tonnes of emissions in 2020-21. The plan is to tighten baselines – so that these facilities need to reduce their emissions (or buy offsets) so that in total they produce 48 Mt/a fewer emissions by 2030. The top 20 emitters are dominated by oil, gas, coal and alumina refining. The facilities may reduce emissions or offset them by buying ACCUs – hence the need for integrity. The companies will be able to produce and sell credits where their emissions are lower than the baseline.

The voluntary market

There has been strong growth in the voluntary surrender of Carbon Credits with companies wanting to claim carbon neutrality for their operations or the products they sell. This market is estimated to be about 15 Mt/a in 2021.

Almost all emission units are cheap CERs (international Certified Emission Reduction units) e.g. wind and solar projects in China and India, for example. There are other registries and it is estimated that there are another two million VERRA and Gold Standard units surrendered and not captured by the ANREU registry.

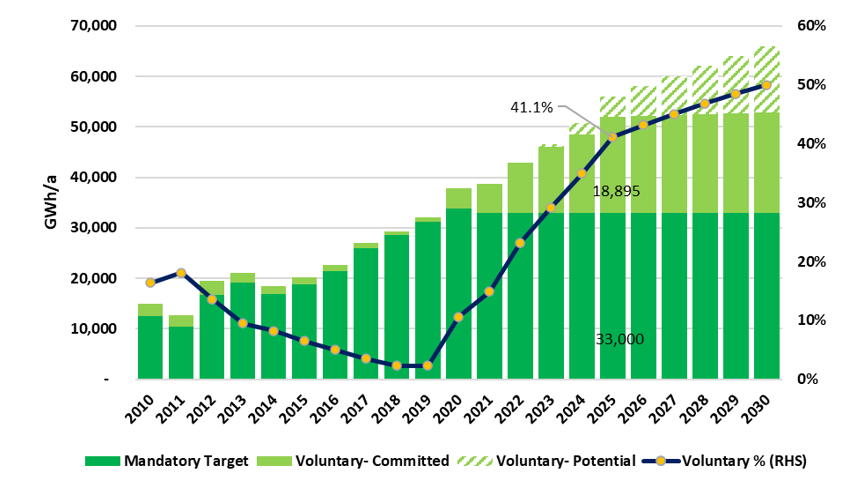

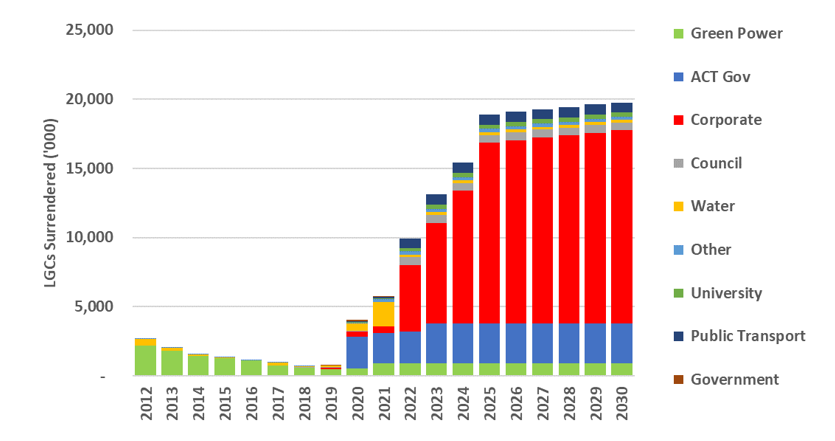

Renewable Certificates (LGCs) What is the demand?

In addition to carbon, a number of corporates and individuals choose to voluntarily buy renewable energy/green power or surrender renewable certificates (LGCs). By 2021, six million certificates were voluntarily surrendered. By 2030, delivery of emissions reductions from LGCs could match those from changes to the Safeguard Mechanism.

The voluntary market is really important and the main growth has come from the corporate sector as shown by the following graph. A large number of companies have bought 100% renewable energy and will aim to surrender the renewable energy certificates on a voluntary basis.

The graph only includes credible and specific commitments so there is potential for the growth to be even greater.

An example of voluntary action and ‘voluntary surrender’ of certificates

The National Australia Bank is a member of RE100, an international initiative by the Climate Group and has committed to be 100% renewable and voluntarily surrender of the certificates. NAB has also joined Climate Active, and claims carbon neutrality since 2010 and under Climate Active must demonstrate that it has surrendered the certificates it needs to.

Climate Active has 387 members that will make claims for their products and services. For example, Coles has zero-carbon beef which means Coles will have bought offsets.

Accountability and transparency is critical

The previous government introduced the Corporate Emission Reduction Transparency (CERT) initiative and NAB is part of that initiative. In 2021, the NAB had surrendered 15,000 international VERs, 18,362 international VCUs, 6,764 ACCUs and 31,875 LGCs

The Initiative reports progress in meeting targets and uses a standardised reporting framework.

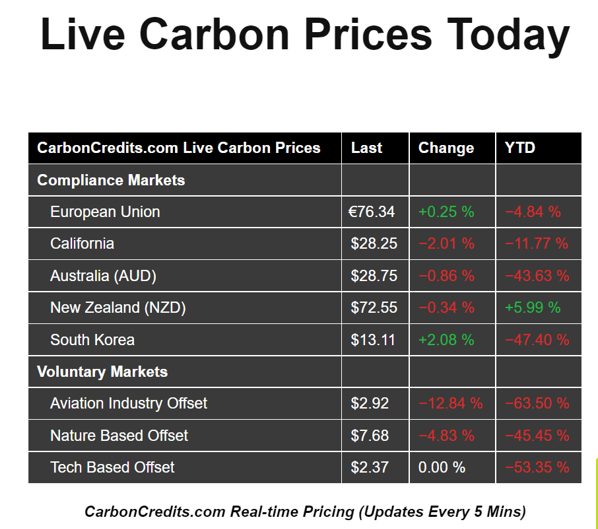

International Carbon prices

International carbon units are trading significantly lower than ACCUs (at Wed 27 July) as shown in the following table.

Making voluntary action additional

The punchline. We need to make sure that voluntary action is “additional”, that is beyond business as usual, and not just making it easier for large emitters to meet their baseline. At present most voluntary action appears to have no meaningful consequence. This leads to a situation which is both disincentivising, economically irrational and unfair.

In updating its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and tabled legislation the Federal Government has stated that the 43% target was a ‘floor’ and that its aspiration was that even more emission reductions could be delivered. Voluntary action (surrender of ACCUs and LGCs) could amount to an additional 44Mt/a of emission reductions and get us beyond 50% reduction by 2030.

What needs to change?

- Voluntary action that results in a surrender of Carbon Credits (ACCU) or LGCs should result in abatement beyond mandated measures.

- Companies involved in ‘voluntary surrender’ should participate in organisations such as Climate Active.

- Companies making carbon or renewable commitments should be held accountable for meeting these. That is, participate in Carbon Emission Reduction Transparency (CERT)

- There should be no double counting of electricity emission reductions – electricity intensity for carbon accounting should net out the voluntary surrender of LGCs (someone else is claiming these)

- We must improve the integrity and the transparency of offset method development and oversight

- There should be limited use of international offsets eg. Indo-Pacific Offsets scheme

Questions and answers

Q: If the revised Safeguard Mechanism allows companies almost infinite offsets, can that be achievable and have any integrity?

- A: (Ric) A significant amount of emissions at the sites could be reduced by the rollout of remote renewable generation as renewables and batteries get cheaper. So it’s unlikely companies will need to buy 100% offsets. However, there should be more than enough offsets if we get the market right. Labor’s Safeguard Mechanism ‘tightening’ does not commence until 2024-2025. If we create a market that people have confidence in, it can be delivered.

- A: (Andrew) In principle I agree with Ric. If offsets are limited to ACCUs, and we restore integrity to the market, then supply will drop from 15 -16 million ACCUs down to say 5 million legitimate ACCUs. Ric is right. Businesses will find ways to reduce emissions. We must ensure any offsets they purchase have integrity.

- A: (Ric) Unlikely to have a problem in the next 4 or 5 years. The previous government announced that people who are contracted to sell their ACCUs to the regulator can back out of their contracts and people are starting to and that’s the main reason why the ACCU price fell. So in the short term, there is an over-supply of certificates.

Q: Many legislative schemes we have in Australia that are establishing market-based regulators require the appointment of members representing a variety of different interest groups e.g. ACCC and AEMO. Would this be something that might fix the governance issues of the Clean Energy Regulator?

- A: (Andrew) Possibly. In the end, we need groups that have expertise in the relevant areas. At the moment there is not enough capacity in and around the Clean Energy Regulator. Obviously, the industry is an important part of the arrangements – they bring a lot of expertise – they have to be at the table. However, at the moment, the governance is dominated by those who are the beneficiaries, and that’s the unhealthy situation. You have to have a broader cross-section of expertise at the table, and there has to be a very special place for independent scientists and independent science, and that’s currently lacking.

Q: At the moment, with the ACCU market, there’s a blurring of the lines between projects with methods avoiding the consumption of fossil fuels and methods that are about planting trees. Is there a principled reason for drawing a line between the multiple types of abatement?

- A: (Andrew) Firstly, anything that’s covered by the Safeguard Mechanism you shouldn’t be able to double-dip. If you’re covered by the SM (Safeguard Mechanism) you shouldn’t be able to generate offsets but at the moment you can. That needs to be moved into a more traditional emissions-intensity type scheme. The next step is OK where do we draw a line? Is there a simple split between emissions avoidance projects and sequestration projects? I don’t think there necessarily is. I think really the test is, can we have high confidence that the abatement is real, that means that there’s an actual reduction in emissions and we can measure it with high confidence, and the second one, which is often forgotten is that additionality won’t occur anyway. And there are certain types of activities where it’s hard to have confidence, such as soil carbon. The reason for that, just to give an example, is the relevant stocks of carbon are naturally fluctuating. In the case of soil carbon, rainfall is the driver leading to relatively large fluctuations. And it’s the same in rangelands, rainfall is driving temporal changes, quite significant changes, in woody biomass onsite through time. And then what you’re trying to do to issue a carbon credit is to isolate a relatively small potential management effect, and any reasonable scientist will tell you, you need a significant number of years, when you’ve got naturally fluctuating background noise, to be able to attribute any management change with high confidence. As a consequence, those areas are naturally difficult and problematic for offset, and it’s not that I am against soil carbon or sequestering additional carbon in the rangeland, it’s just that it’s a higher risk activity and therefore it doesn’t naturally lend itself to offsets. If you want to get at those abatement opportunities then you need to use another instrument. And I think we need to apply a similar mindset throughout the rest of the economy to find out which opportunities are high confidence and which are not, rather than draw arbitrary lines.

- (Ric) I think that there wouldn’t be a case to include a reduction in energy if we had a broad-based emissions trading scheme that had all (most?) sectors covered then you could only produce offsets from sectors that aren’t covered by the emissions trading scheme, but the problem is our whole energy and greenhouse policy has been a quagmire and we don’t have any effective policy, so we’ve got to make do with what I call the second best option. And so to me it’s about reducing greenhouse gas emissions and that’s the key thing and if you can do it through planting trees or reducing energy use, that’s fine.

Q: Are the international units better than ACCUs? Would moving to these alternative international methods rather than having a bespoke Australian scheme improve integrity?

- A: (Ric) Some are driven by international schemes, in particular the clean development mechanism, I think Australia is unique in a way because we’ve been at the forefront of the development of a lot of this activity.

- A: (Andrew) The problems we have encountered in Australia are not unique. Most offset schemes have encountered similar problems. We’ve claimed we have the best scheme in the world. I don’t think it’s true and I don’t think adopting methods and processes from overseas, or just allowing all international methods to apply in Australia will make anything better. In some cases, I know as an absolute fact, that it will make things worse. One of the issues is, particularly when you get to the land sector, the Australian environment is different from other environments and you actually need methods that are tailored to the Australian circumstance. A good example is that there’s a real opportunity in Queensland to have what’s known as a ‘Category X’ Avoided Clearing method there. The idea is to target areas that are able to be cleared under Qld land-clearing rules. A generally designed method that’s completely international can’t have that sort of specificity that you need for the Australian circumstance. So while it sounds like it might be an attractive option, I don’t really think it is. And it could make things worse.

Q: For those without solar panels or an EV, is it worthwhile offsetting their home and car with various providers including groups like Greenfleet or others? And what do people need to check for if they are going down the offsetting path?

- A: (Ric) It depends on what you want to achieve. The highest standard would be an ACCU with a method that has integrity. At the moment, savannah burning is being sold at a premium in the market but perhaps that’s also suffering from integrity issues, Andrew?

- A: (Andrew) For integrity, the first thing I’d be asking for is transparency. If it’s trees, you want to know where they are located, you want them to show you everything – their offset reports. If people aren’t willing to do that then that should be a massive red flag. Beyond that, it does get very hard and you need to have specialised skills, knowledge and data to do decent due diligence and I think a lot of corporates trying to do the right thing have encountered problems caused by a lack of transparency in the system. As a consequence, they are now spending significant dollars doing exactly this sort of due diligence. So what I generally advise householders and other small buyers to do is stick to the safe territory. Environmental planting is safe. I’d have no problem buying credits from an environmental planting project or a mob like Greenfleet for example, who plant trees, make sure they are put in decent places and maintain them over time. That’s not to say there aren’t other good projects. There are even good human-induced regeneration (HIR) projects out there. You’ve just got to know exactly what you are looking for. And I should say that while a lot of people criticise landfill gas, I know there are a significant number of high-integrity landfill gas projects. This makes the story quite difficult. I’ve been out there criticising large landfill gas projects but I support the majority of landfill gas projects. It’s not an easy answer, but for those who aren’t experts, I’d say stick to the safe territory.

- A: (Tim) Fundamentally it comes down to trust, and that requires transparency, and that requires engagement, but models like Greenfleet where they also do the environmental planning, biodiversity impacts, and ways to try and maximise all of the other benefits means that even if your carbon numbers end up being slightly fuzzy, you know you’ve got all the other angles there, but it’s ultimately about finding the stories that you can trust.

Q: Is there a good rationale for providing offsets for avoiding deforestation?

- A: (Andrew) It comes back to confidence. Do we have high confidence that those areas would be cleared if they didn’t get carbon credits? Are there any places where we can have that sort of confidence? I think we missed in relation to the existing avoided deforestation method in western NSW. I’m not saying that there isn’t some additional abatement that we’ve got out of those projects. But on the whole, I don’t think that the data suggests that we have. And that issue you raised just then is one of leakage, and there seems to be quite a lot of data that suggests that around the time those projects started getting payments or credits out of the avoided deforestation method, that it coincided with a spike in clearing out in that country and so there seems to be some, at least anecdotal, evidence that leakage wasn’t isolated to the one landholder featured in the ABC story, it could have been a number of others. Having said all those negative things, I’m a supporter of a method around Category X in Qld where 300 to 400 thousand hectares are cleared every year. If you’ve got Cat X land in Qld and it has certain attributes like it’s relatively flat and in the higher rainfall zones, and it’s been cleared before, then there’s a very high probability that it will be cleared again. But we have to be really cautious with this. It is one of those areas where it is very easy to get it wrong. And if you get it wrong, you can get it way wrong.

Presenter slides

- Tim Baxter Carbon Credits Intro Jul 2022

- Andrew Macintosh ERF integrity issues Jul 2022

- Ric Brazzale Carbon Offsets Jul 2022

More on Carbon

Other Lighter Footprints pages on carbon can be found here.

What’s On next?

For the Lighter Footprints What’s On page, go here.